In addition to the Executive Summary below, you can now view the entire report in PDF form.

Executive Summary of the Basin Wide Fish Assessment

Upper Feather River Basin Fisheries Assessment and Restoration Strategy

A Cooperative Project:

Sierra Institute for Community and Environment

Feather River Chapter, Trout Unlimited

June, 2018

Vincent Rogers

Ken Roby

Michael Kossow

Executive Summary

An assessment of Rainbow Trout distribution and habitat condition was conducted for the Feather River watershed upstream of Lake Oroville. Physical and biological attributes were used to rate the relative condition of 121 sub-watersheds and 64 reaches. Ultimately, the assessment was driven by projections of future conditions for native trout, based on climate change models used to estimate thermal and hydrologic factors. This analysis produced ratings of exposure applied to each subwatershed. Estimates of exposure and condition were combined to produce priorities for restoration based on relative resilience of subwatersheds and associated stream reaches. Trout habitat was rated based on stream temperature, habitat connectivity, biological indicators and watershed condition. Biological indicators included distribution of rainbow, brook and Brown Trout; presence of two pathogens with a history of debilitating impacts on trout in the basin; and presence of three invasive gastropods. Watershed condition was rated using indicators of road impacts (near stream road density and frequency of road crossing), wildfire, number of water diversions, estimates of baseflow diversion and low gradient channel condition.

Review of survey records, monitoring, published reports and literature were used to determine distribution of Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss), Brown Trout (Salmo trutta) and Eastern Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis. Use of survey records for these species was supplemented by sampling for environmental DNA from 68 stream and river sites. In addition to fish, eDNA was used to detect presence of New Zealand Mudsnails (Potamopyrgus antipodarum), Zebra Mussels (Dreissena polymorpha) and Quagga Mussels (Dreissena bugensis). These invasive species have been found in waters relatively close to the basin. eDNA analyses for the pathogens Myxobolus cerebralis and Ceratanova shasta was also performed. Results found no positive tests for invasive snails. Positive eDNA results for whirling disease and Ceratanova shasta were found at sites where previous studies confirmed presence of the pathogens. Results for trout species showed strong correlations between eDNA results and presence based on survey and monitoring records.

Examination of historic climatological data found trends of warmer temperatures, less snow and lower streamflow in the basin. The impact of continued warming on future habitat conditions was assessed using the Basin Characterization Model. Projections from two climate scenarios were used to estimate future air temperatures, runoff and snowpack across the basin. The NorWeST stream temperature model was used to estimate historic and future stream temperatures. Ranges for thermally suitable and optimum conditions for the three trout species were developed and compared. A combined rating of likely future conditions for trout was conducted using projected runoff (representing available habitat), snowpack (maintaining baseflows), and stream temperature. This assessment was used to place sub- watersheds into four exposure classes (Figure i).

Figure i. Subwatersheds grouped into three Exposure Classes

Indicator information was aggregated to provide relative ratings of condition for each sub-watershed. Condition indicators used in the rating were the densities of stream channel road crossings and roads within 30m of a channel, the number of diversions and amount of streamflow diverted, the condition of low gradient stream channels and the connectivity of stream habitats (presence or lack of barriers to fish movement). Available stream monitoring data was used to explore the relationship between the condition factors and habitat conditions and provided justification for their use.

Results revealed a range of conditions within sub-watersheds. The few watersheds with no or very few roads and no stream diversions were rated in the best condition. Typically, watersheds in the higher elevations (usually with steeper terrain) had less roads and fewer diversions. Presence of whirling disease, and presence of high severity wildfire (in past 15 years) were deemed to be important condition indicators. They occurred in relatively few locations, so were not included in the basin-wide rating. Rather they are noted where present in watersheds ultimately rated as priority for restoration. Rainbow Trout were found in every sub-watershed and reach, and brook and Brown Trout in most areas. Only 4 sub-watersheds are thought to support only Rainbow Trout.

Stream reaches were generally found to be in poor condition. Reaches in the headwaters are strongly influenced by roads and had highest densities of channel crossings and near stream roads. Mid-elevation reaches located primarily in the large meadows of the basin are the site of considerable diversion of baseflow for agricultural use and displayed warm stream temperatures. Farther downstream, water temperatures in reaches were typically too high to provide highest quality habitat for Rainbow Trout.

The assessment was used to identify priority areas for habitat protection and restoration. Concepts from the Trout Unlimited and FEMAT strategies for protection and recovery of aquatic species were

employed. Both approaches emphasize protection of areas in the best condition, and reconnection and restoration actions targeted at priority habitats. Geographic restoration priorities were based on the relative resilience of sub-watersheds. Resilience was assessed by combining ratings of exposure and condition. Highest priority for protection and improvement was given to areas that possess the lowest exposure (best streamflow, snowmelt and thermal) characteristics; and the least disturbance (best connectivity, fewest diversions, fewest roads). In all, 48 sub-watersheds were classed as priority, with 5 receiving a rating of very high resilience, 21 with high resilience and 23 with moderate resilience (Figure ii). These areas were typically sub-watersheds at high elevation where projected changes to snowpack and stream temperature would be moderated. As a result, sub-watersheds with highest resilience tended to be clustered. Reaches that provide connection between sub-watersheds within the resulting clusters, and between clusters, were rated as highest priority for protection and restoration. Actions that could be applied to maintain or improve resilience of priority areas are recommended and discussed.

Results from eDNA surveys for whirling disease confirmed the presence of the pathogen at several locations in the basin. This disease has had devastating impacts on fish populations in the basin, and elsewhere in the western United States. Currently, there are no efforts or actions by any agency or party to contain or manage whirling disease in the Feather River. Development of a plan or strategy for containment of the disease is identified as a top priority for restoration in the basin.

The condition ratings provide a starting point for identifying other actions most likely to maintain or improve resilience in the priority areas. Subwatersheds in the highest priority class are targets for protection as investments in restoration actions are not needed to maintain their resilience. Subwatersheds with low road condition ratings could be improved with treatments aimed at disconnecting road-channel delivery of fine sediment and runoff; work with water users on fish screens and instream flows are of high priority in areas with diversions. Improving connectivity by providing for fish passage at key man-caused barriers (typically road crossings with culverts) is priority in areas with low connectivity and appears to be the most practical way to improve resilience in the short term.

Figure ii. Priority subwatersheds for restoration, by resiliency (priority) class.

Conservation Strategies in the Feather River Basin

Feather River Trout Unlimited was recently featured in The Sacramento Bee for their efforts on identifying invasive species and pathogens. Jane Braxton Little, a freelance writer, covers science, natural resources and rural Northern California from Plumas County, describes the new face of conservation: choosing which areas to conserve and which to let go with the changing climate. Our very own team of scientists are doing just that in the Middle Fork of the Feather in Sierra Valley to Yellow Creek in Humbug Valley.

Ken Roby, who is a retired aquatic ecologist from the U.S. Forest Service, is heading up the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment. He is using a new identifying technique called eDNA to establish a list of rivers or creeks who have been hit by diseases or pathogens.

Instead of focusing our efforts on getting rid of invasive species or pathogens, we are instead choosing to protect areas where our native fish can thrive and repopulate. Little gathers from our very own Cindy Noble, “We don’t want to dump a bunch of time and money into a problem we can never fix,” said Cindy Noble, chair of Trout Unlimited’s Feather River Chapter. “We’re not going to do this the stupid way.”

Read the entire article, Climate change is forcing conservationists to pick winners and losers. How to decide?, By Jane Braxten Little here: http://www.sacbee.com/opinion/california-forum/article192668824.html#storylink=cpy

FIELD SAVVY…

Indian Creek below Antelope Lake; the fall splendor is made more remarkable by the contrast with the burn scars of the Antelope Complex Fire.

The other day myself and a few other Feather River Trout Unlimited folks had the opportunity to volunteer with California Department of Water Resources and California Department of Fish and Wildlife for a day of electrofishing on Indian Creek below Antelope Lake. I like to look at such efforts as representing a willingness to assist those that have helped with the development of my own work over the last year.

You’ve heard of cattle drives? This is what a trout drive looks like. Perhaps a few too many cooks in the kitchen though.

Even if it required a few hours of work the preceding weekend, a day in the field was a nice respite from the long hours spent at the computer drawing fish maps, developing assessment frameworks, and planning eDNA sampling. While fish numbers in the creek were not so great, it was overall a lovely day for the task at hand and I learned and relearned a few harsh lessons about fieldwork.

First, a brief history of the reasons why we were there to monitor the fish populations in the first place. Antelope Lake was constructed as mitigation for the lost recreation opportunities that stemmed from the creation of the State Water Project, i.e. Lake Oroville. Part of that mitigation was the maintenance of a fishery on Indian Creek below the lake, for which minimum in-stream flows were established. California Department of Water Resources has been regularly monitoring the fishery since the early 1970s in accordance.

Feather River Trout Unlimited Members assist DWR staff with processing fish, taking measurements and weights.

With the recent severe drought, flows from Antelope Lake have decreased below their regular minimum making it more important than ever to monitor the fishery. I had the opportunity to volunteer last year as well, where results showed a decline in fish abundance compared to years prior. With the near-normal winter of 2015-16 I hoped that things would have improved but, sadly, they had not. Fish numbers were even lower than last year, illustrating the long-term impacts of drought and importance of maintaining annual in-stream flow to support fisheries below reservoirs.

The lessons of the day were not wholly scientific though. It seems time at the computer desk has allowed me to grow a bit soft to the field (although I netted my fair share of fish!). Lesson one: if you leave your dog in the car, place your fly rods in their cases! Lesson two: know where your keys are at all times! Lesson three: make time to enjoy a cup of coffee!

That’s right, while my young lab-spaniel mix, Bolt, managed to stay calm during electrofishing at the first station, results at the second station were not as positive. Forced to content himself with a rawhide while I was out of sight down at the creek at the first station, Bolt had a clear view of the work at station two and apparently it was just unbearable… unacceptable… that he might not be allowed to join in whatever fun we were obviously having down there. Result: two thrashed fly rods!

Indian Creek tends to be predominated by brown trout rather than native rainbows, although the mix is usually just about even. Sampling produced some healthy fish, as seen here, but the numbers were just not as good as they should be.

AND… yes, later on, after cleaning up the mess of broken graphite in my car (such that Bolt might not be tempted to take the next step and actually consume the pitiful fragments of my evening plans) I discovered something grave! My keys were in neither pocket of my jeans! Nor were they in either boot of my waders!

Long story short, after a generous ride from California Department of Fish Wildlife staff, I found myself sitting in my waders in downtown Taylorsville sipping possibly the most delicious latte I’d had in years as I waited for my spare key.

Bolt. Promising youth, psychological warfare ninja

From the perspective that all experiences are to be learned (or relearned) from, I’m chalking the day up to a success! While the fish numbers we not as good as I had hoped, it’s always nice to get out in the field, see some beautiful weather and landscapes, keep up with the fish Jones, and make a warm cup of coffee all the more worthwhile. I needed a new fly rod anyways…

IN GOOD HANDS…

Feather River Trout Unlimited Member, Holly Coogan, delivers a pointer here and there for up-and-coming casting champion.

…introducing younger generations to cold-water conservation.

The mission of my host organization Trout Unlimited is to conserve, protect and restore North America’s cold-water fisheries and their watersheds. Implicit to this mission is that fisheries and watersheds remain intact and available for the enjoyment of future generations. One of the greatest ways to introduce the value of conservation into the minds of younger individuals is to allow them to experience the outdoors through recreation. Fly fishing is a fun recreational outdoor activity but is also a great means for teaching the concepts surrounding ecological balance that lead to realizations about the value of conservation.

I recently assisted with a fly fishing demonstration for a local 6th grade classroom as one part of their recent field trip to Lassen National Park. We visited Manzanita Lake on the northwest corner of the Park to provide the students with an introduction to the sport.

Speaking from my own experience, the seemingly complex nature of fly fishing can sometimes pose as a barrier to entry to the sport. This may be especially true for a youngster. While there is an obvious and attractive grace to the practice of angling with the fly, the mystique surrounding the techniques for casting and the apparent wealth of knowledge required to ‘match the hatch’ have rendered many an entry-level fly rod dusty and neglected at home while the spinning gear gets all of the action on the water. While it may take a season or two before you’re casting confidently and consistently catching fish, it doesn’t take make much to strip the sport of its overwhelming complexity.

To that end, we started our day with the very basics, casting practice using dummy flies with no hooks. Much to their surprise, the youngsters found they were quite capable of placing the fly where they wanted to in just a short amount of time. Casting? Check! Next we donned our entomologist hats to learn about what exactly it means to “match the hatch.”

Young fly casters deftly pursue their catch.

Quite simply, “matching the hatch” involves turning over a few rocks or logs to see what the bug neighborhood looks like. We found mayfly nymphs, caddisfly larvae, dragonfly nymphs, snails even a great specimen of Belostomatidae, variously called giant water bug, alligator ticks, and even toe-biters. While the offer of one intrepid youngster to hold the large beetle was greeted with bloodshed at the tips of the bugs pinchers-like forelegs, all agreed that the specimen would amount to something like Thanksgiving Day dinner for a trout. While the pain of the wound quickly subsided, the young man’s surprise did not as he continued to inspect and show of the minute punctures at the end of his index finger.

Next, we checked in our fly boxes to see what we had that might successfully deceive a cruising trout. The kids deliberated over which particular flies could best represent some of the bug life we observed. We tied some of ‘em on and before long most all of the class was confidently shooting hopeful casts with real flies, and real fly rods out to the unsuspecting trout of Manzanita Lake! And with that, the intimidation surrounding fly fishing had all but completely dissolved.

Yes, some children arrive confident and some even experienced with fly fishing in the past but the real pleasure in introducing kids to the sport of fly fishing (or any other manner of outdoor recreation for that matter) is providing an experience to children that may never have gone fishing, much less on the fly, or that have never even had the opportunity to experience the beauty and wonder of the places where fly fishing takes place. Places like Lassen National Park, for instance.

A young angler smiles between casts.

While the wary, educated trout in this catch-and-release only lake were not fully cooperative (I myself failed to make a cast that didn’t spook the fish), the day was undoubtedly successful in terms of the learning experience. True, it always helps to catch some fish but it matters less than you would believe. The kids didn’t seem to mind the lack of catch and were quick to embrace the whole experience. For the kids that pursue the sport themselves, fishless days will be a common occurrence. Even if we do get skunked occasionally, we can always reflect on the things we’ve seen, experienced and learned that day. When we help younger generations see these sights, have these experiences, and learn these lessons we place the future of a sport, and the conservation of its settings, into good hands.

Mt. Lassen looms over Manzanita Lake, located on the northeast corner of Lassen National Park.

FISH STORIES TOLD HERE!

The North Fork Feather River below Lake Almanor- the section of the North Fork from Almanor to Caribou is often cited as having been one of the premier fisheries in the area. Once home to a healthy population of naturally reproducing rainbow trout averaging 14-16 inches, the fishery in this stretch is now a fraction of it’s former glory. This is due in part to wildfire (notice the burned stands on the horizon) but primarily due to reduced flows, the result of a variety of safety and efficiency concerns with hydroelectric operations on the system. Prescriptions for restoring the fishery on all or parts of this section have been contentiously debated.

Angler ethnography in the Upper Feather River Basin…

One of the most important components of informed fisheries restoration is establishing a historical reference for condition and distribution. A unique aspect of my project is that we are including anecdotal information from long-time anglers familiar with the rivers, streams, and lakes of the Basin to help inform this historical reference.

Efforts to establish informed knowledge of fish distribution in other areas have mostly relied on the survey records of agencies tasked with monitoring. While this is true of the UFRBWA as well, we are also including information from anglers in order to collect information on bodies of water not covered by the available survey records. The knowledge held by these folks is the result thousands of hours of “sampling,” some reaching farther back than the official survey record, resulting in an informative and often untapped source of data.

During the interview process, I sit down with anglers and we run through a list of questions that I’ve developed as guidelines for the discussion. Each interview is recorded and transcribed to ensure that any and all valuable information is captured. Distribution of fish species discussed during the interview is then traced onto a map with colored highlighters by the angler. Each of these records is then incorporated as data in digital maps showcasing fish distribution, alongside data obtained from the official survey record.

To date I’ve interviewed 7 “anglers,” which in reality range from your average hobby anglers, to fly shop owners, to professional fishing guides and retired agency staff. The list of willing future participants continues to grow. As it turns, out people like to tell fish stories.

More importantly, people like to express their concerns about their favorite fishery and their theories about factors affecting its quality. So, as a secondary component, the interviews also serve as a venue for community outreach in which I can ask folks about their observations and how they have changed over time. These observations can sometimes provide significant insight revealing the impacts and effects of both natural changes and management practices on a given fishery. As a result, anglers have also provided information on areas in the Basin that have a significant need or opportunity for restoration.

The Middle Fork Feather River near Graeagle- while much of the lower length of the Middle Fork is a designated Wild and Scenic River, some anglers believe that development and changing land use in the upstream reaches has negatively affected the fishery in those areas over recent years. Angling represents a valuable attractant for tourism in the area.

One of the great pleasures of engaging in this work is to see the passion of these dedicated anglers, conservationists, and outdoor professionals. Some of them have been consistently fishing the same streams since they were small children, representing many decades of observation. Others may have many fewer decades of observation under their wader belt, but have fished the waters very frequently in recent years. These individuals can provide valuable insight concerning significant changes and impacts in the more recent past, as well as those that are actively occurring now. Often times the conversation can be as inspiring as it is informative.

While both work and pleasure have brought these folks to the waters of the Upper Feather River Basin, an overarching theme is their shared passion for the ecosystem. A discussion about where a 4 in. rainbow trout may live in some backcountry headwaters easily transforms into to a discussion that is much broader in context. Sometimes it evolves into an examination of the greater political economy of natural resource management. Other times it becomes a mental projection back into geologic time, wherein we attempt to imagine a far colder and wetter landscape and a climate that would allow fish to migrate up glacier-fed torrents to places that have now been long inaccessible. It’s refreshing to know that others share these thoughts; that something as small and insignificant as a single fish can be emblematic of how politics can dangerously constrain and misguide resource management, that that creature is potentially an evolutionary wonder.

It’s sometimes easy to get weary of the long hours in front of the computer screen that have been necessary to begin compiling all of the information that is going to go into the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment Strategy. In my experience thus far, though, there have been few things more encouraging and invigorating than hearing the stories, experience, and concern of the anglers I interview. Plus, I’ve picked up a good fly or tip here and there. And… I may have heard a whopper or two, I suppose.

LATE SUMMER IN THE LOST SIERRA…

Western Chokecherry, and other wild berries, have ripened by late summer, an annual reminder that Fall is near (and that it might be time to make syrup).

Late-summer has its signals everywhere and for every year…

I started my Sierra Fellows experience in October of last year when just a few weeks into my term I woke to snow in the morning. Since then I’ve learned not only a lot about the fisheries of the region but also about the way of life in the Lake Almanor Basin and the rest of the Lost Sierra.

While I’ve lived in the foothills of the Sierras and Southern Cascades off and on throughout my life, I think coming back to rural mountain living in the context of serving as a Sierra Fellow, wherein I am in part supposed to learn about a community and strive to improve it in some way, has left a unique impression on me.

Perhaps, I can’t rightly separate it from any other late Summer interval in the past, but it also seems like my perspective has shifted from noting the changes prior to rather than after they occur. When I previously lived in rural mountains I was a child, for one thing, and I think that my observations were more reactive, as in ‘oh, school has started!’ or ‘the days are so short!’ Now I find myself noticing things like the ripening wild berries, the shrinking creeks, fawns losing their spots, mounting piles of firewood around town, and the tapering off of the crowds of weekend visitors.

In late summer, Lake Almanor’s rainbow trout begin to seek refuge near cool tributaries and submerged springs. Fish like this one will readily take a grasshopper imitation even in the warmest hours of the day when few other anglers are around.

Of course, given the focus of my work I’ve noted things about the local fisheries as well. The trout have moved to areas of the lake where there are springs or where tributaries enter; places where they can find cooler temperatures and more oxygenated water. The thousands of juvenile smallmouth bass that lined the shores, providing constant sport for the light fly rod, have now moved offshore. Having grown over the summer to a size that makes them less susceptible to predation they can now safely enter the deeper water to find the food they need to continue to grow.

Similarly, It seems like populations of juvenile trout have thinned in the Hamilton Branch since the early summer. I suspect this trend is probably also influenced by competition. As individual fish grow the competition for food increases and some fish move down to the lake in search of better food availability. Some of those fish will perhaps return to the Hamilton Branch and its tributaries to spawn next Spring or the one thereafter.

While I welcome the turning of the season for a number of reasons -the quality of Fall fishing, the colors of the leaves, and holidays with friends and family, just to name a few- I find myself somewhat melancholy about summer’s passing. Here again, is this summer any different than the last? It’s not just about no more weekend community events (and associated BBQ) for a few months, or dreading cold, pre-dawn mornings, or even project deadlines. It’s more to do with the fact that summertime in the Lost Sierra encompasses so much of what brings people to visit and stay in places like this.

Even late-summer’s most necessary and rigorous activities can be a welcome refrain for the frustrations of the GIS workbench.

Despite all of the challenges that are associated with living in rural mountain communities the quality of life is in truth in many ways unmatched. So as my first term as a Sierra Fellow nears a close, I already find myself looking forward to my next and to what can be achieved with the communities I am now a part of. I guess a part of me is even looking forward to the Fall colors, and, heck, maybe even to the first snow!

Rainbow Trout: What, Exactly, Are We Protecting?

On a recent weekend trip through the Pacific Northwest I stopped at a magical place in Portland known as Powell’s City of Books. With four floors of reading material, I couldn’t help but saunter a bit, even taking a moment to browse the rare books collection that included, among other marvels, an edition of Pliny the Elder’s Historia Naturale circa the 1600s.

In the end, though, I was choosing between three books: a survey of global stream ecology, an American Fisheries Society survey of watershed restoration practice, and a narrative work by Anders Halverson, entitled An Entirely Synthetic Fish: How Rainbow Trout Beguiled America and Overran the World. Pragmatism aside, I chose Halverson’s work (perhaps I was just seeking relief from my complete immersion in scientific literature of late). It has proved to be not only an entertaining read and valuable history lesson but also a tremendous thought exercise in relation to my own work.

Livingston Stone established a hatchery on the Upper McCloud River (in the Sacramento River Basin) in the late 19th century. Initially established to restore Atlantic salmon stocks with Pacific salmon species, his hatcheries would become some of the first from which rainbow trout would become stocked on a widespread basis. (Photo: CDFW)

Patty Limerick, the Faculty Director and Chair of the Board of the Center of the American West at the University of Colorado Boulder, accurately frames Halverson’s narrative surrounding the rainbow trout’s world takeover as a valuable precautionary tale. Natural resource management, particularly in the American West, has had no shortage of trial and error. Take the disastrous results of the early efforts of influential conservationists to control predator populations throughout the West, for example.

The decisions of well-meaning resource managers to eradicate predators resulted in immense numbers of starving and diseased elk, deer and antelope across the West. Because their numbers were no longer controlled by predators like bears, wolves, and lions, the game animal populations exploded and then subsequently collapsed to even fewer numbers than ever. Predators played an integral part in maintaining overall herd health, something of a revelation at the time.

This marked the beginning of a new era of understanding in ecology, one that would begin to acknowledge the great complexity of natural systems. Halverson’s book contains numerous lessons about both the complexity inherent to natural systems as well as the cascade of error in management that has (and still can) arise when this complexity goes unacknowledged.

M. Cerebralis, the agent parasite for the often fatal whirling disease, is thought to have come to the U.S. from European hatcheries in the 1950s. Once here, it quickly became a problem for hatchery operators and, due to wanton stocking efforts, a threat to wild trout populations. While there are a few locations in the Upper Feather River Basin where M. cerebralis is known to be found, UFRBWA aims to establish understanding of Basin-wide distribution of the pathogen through it’s eDNA sampling effort. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Tracing from the fish culturing practices in 18th century Europe, he elucidates how fish propagation later became a matter of national importance for the newly-formed United States of America. He moves on to describe efforts to rebuild decimated Atlantic Coast fisheries with Pacific salmon stock from our own neighboring Upper Sacramento River. Happenstance amid those efforts found the rainbow trout to be a hardy, aggressive, easily-domesticated alternative when efforts to stock other Pacific salmon failed.

Halverson explains how social convention elevated the rainbow trout to the realm of premier game fish, the pursuit of which defined a gentleman, and how, in the end, the longevity of such conventions prompted resource managers to enact sometimes disastrous management decisions in favor of rainbow trout over other native biodiversity across the West.

The most potent lessons found in the history of artificial propagation of rainbow trout can be found within the wholly unintended, and for a long-time unnoticed, consequences of proliferating the species. Halverson outlines the story of three of these devastating wake-up calls for fisheries managers.

The first, involves the spread of Myxobolus cerebralis, the agent parasite that causes (the most-often fatal) whirling disease, first through hatchery systems all across the world and subsequently into the wild due to wanton stocking practices. The second is the significant loss of biodiversity among the other native salmonids of the West due to hybridization with rainbow trout, not to mention, the dilution of genetic stock among wild populations of rainbows themselves. The third is the un-monitored impacts of rainbow trout stocking on taxa other than fish, most notably the endemic amphibian species of California and the rest of the West.

Extensive stocking of rainbow trout has led to the proliferation of hybrids like this ‘cutbow,’ a common occurrence in the native range of the cutthroat. Hybridization of hatchery stock with wild rainbow trout poses the risk of diluting the genetic diversity of rainbows across the species’ own native range. As part of UFRBWA I have been attempting to establish the relative magnitude of stocking efforts across the Basin, in an effort to determine where observed wild populations of rainbow trout may have incurred little or no hybridization. (Photo: Wikipedia)

Most of this grand history lesson applies directly to the fisheries of the Feather River Basin. Extensive stocking has established non-native trout and other fishes in the Basin, efforts that concomitantly also introduced M. cerebralis. The stocking of rainbow trout has also certainly resulted in hybridization with true native populations, the extent of which is not known (although a recent study sheds a favorable light). Eradication efforts have taken place in the Basin to eradicate fish in the preservation of native amphibians.

So, amidst this history of inadvertent (and, yes, sometimes advertent) blunder of uninformed fisheries management, particularly surrounding rainbow trout (the eradication of which is a huge concern in water bodies where they are not native across the globe), the question arises: “What are we protecting?”

Well, at its core, the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment and Improvement Strategy is meant to be, in small part, counteraction against this history of uniformed fisheries management strategy. The result, hopefully, will be the right knowledge and information to know where we can achieve the most bang-for-the-buck in protecting and improving wild rainbow trout populations here in their native range.

Mountain yellow-legged frogs are native to the Sierra Nevada. In the mid-90s Roland Knapp, a researcher working with the University of California and California Department of Fish and Wildlife discovered that the extensive fish stocking of high mountain lakes in the Sierra Nevada had likely decimated the species. Extensive efforts to reverse that trend are now underway. The results of the UFRBWA may be used in comparison with the results of similar efforts surrounding other taxa to ensure that fisheries restoration does not result in the decline of other species of concern. (Photo: Wikipedia)

To the greatest extent possible we’re hoping to account for the intended and unintended consequences of historical decisions in fisheries management to ensure we’re doing so effectively. We think that this can be accomplished by identifying the distribution of pathogens, probable populations with low or no hybridization, as well as accounting for the impacts on other native taxa, before expenditure on any restoration can take place.

Often when I speak to people about my work, a similar set of questions arises. The first questions relate to the decline in stocking efforts by resource managers. People also often allude to the contentious management practice of poisoning water bodies (often done in the past to ensure the success of new stocking efforts). They often point out the folly of emphasizing continued preservation in systems that are, arguably, so altered that it is illogical to do so.

It’s true, in reality there exists a history of resource management that will be impossible to escape. Many of the decisions being made by fisheries managers these days are all part of effort to proceed with caution until the trajectory of this history is better understood.

One of the graces of Halverson’s work is that it distills the complexity of a particular history, that surrounding the propagation of rainbow trout, into a compelling narrative. It offers a resource for people like myself to share with others in an effort to provide contrast with business-as-usual management practices based on social convention rather than an understanding of ecology. In many ways, it sheds a real light on the value and necessity of efforts like the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment and Improvement Strategy.

Better than that, it’s not a scientific journal article.

FISHTHINK AND THE VALUE OF COLLABORATION IN FISHERY RESTORATION PLANNING…

It takes a number things, most importantly, clean, cool, oxygenated water, to allow fish like this little Hamilton Branch rainbow, to thrive. It also takes the knowledge of many to fully understand what’s happening in a given body of water and though it may not always be apparent at the onset, perhaps what’s most important is that we’re trying, together.

The Upper Feather River Basin is a place that all at once contains incredible resource values but is also severely impaired. These two things seem to be readily affirmed by those that live and work here and especially by those that work closely with or live for the enjoyment of these valuable resources, including the Basin’s fisheries. While there is often a consensus on the type and severity of issues surrounding natural resource management issues or deficits, it is often rare that consensus will transition to meaningful collaboration. However, this is precisely the goal of my Fellowship.

As of late, I’ve been scrambling to match the calendar and catch the ears and minds of agency staff working on issues related to fishery health in the Upper Feather River Basin. The field season has begun (for myself included! Hooray!) which makes it ever more of a challenge to coordinate the more than 20 “fish folks” who attended and contributed at the first Technical Advisory Team meeting in April.

The idea for the formation of a Technical Advisory Team to help with steering of the UFRBWA has been based on two implicit goals: to 1) harness the experience, expertise and opinions of natural resource professionals working in the Basin to ensure the development of a rigorous analysis of fishery condition; and 2) to build stronger working relationships inside this network of professionals. In short, our goal is to facilitate the development of a broad consensus on fisheries management, and then move into informed fishery protection and restoration actions.

Collaborating with a volunteer Core Group comprised of a representative subset of those original 20 or so professionals, I’ve been at work selecting specific indicators of fishery and habitat condition, and trying to assemble them into a meaningful cumulative assessment of fishery health and the factors that affect it. This assessment will help to reveal what areas of the Basin should be targeted for restoration or protection efforts.

Most of the development of the assessment, including selection of indicators, scale, and data sources, has been based on the input of these experienced and expert contributors. While the resulting synthesis of knowledge will surely be significant, it has also become apparent throughout this process that the true value of this collaboration is greater than even the original intended outcome.

This project is not the first effort to coordinate collaboration over watershed health in the Feather River Basin. Plumas Corporation and the Feather River Coordinated Resource Management group (FRCRM) have been working on watershed restoration and monitoring, particularly focusing on the meadows in the eastern portions of the Basin, since 1985. The efforts of Plumas Corp. and FRCRM have achieved significant collaborative restoration success.

Additionally, the effort is currently underway to rewrite and improve the Feather River Integrated Regional Water Management plan (IRWM). The goal of the IRWM is “…to effectively perpetuate local control and regional collaboration to provide stability and consistency in the planning, management and coordination of resources within the Upper Feather River watershed. To implement an integrated strategy that guides the Upper Feather River region toward protecting, managing and developing reliable and sustainable water resources.”

While the conservation and improvement of fisheries can well be considered to be implied objectives of these two efforts (in fact, the inception for the UFRBWA was partially due to Feather River Trout Unlimited participation in the IRWM planning process!), many resource staff and concerned citizens saw there was still a void for a collaborative effort or group that was fish-centric in its focus. Others felt that beyond that any fish-centric efforts weren’t appropriately large enough in scale.

So, in one sense, the true value of this collaboration is the improved working relationship of folks working with fish in the Basin. This in turn means fishery health is well represented as an explicitly important concern that can be integrated with other collaboration efforts.

EVOLUTION OF A FISHERY CONDITION ASSESSMENT PART III: A MATTER OF SCALE

In the last stage in the Evolution of a Fishery Condition Assessment series, I discussed the importance of individual indicators for describing watershed and fishery condition as well as the qualities that make an indicator ecologically meaningful. Another important consideration in my project work is scale. For our assessment, we therefore have to consider at which scale or set of scales each indicator operates.

Some indicators affect a watershed at the landscape level, while other indicators are only important in the immediate area of the stream. Some indicators may also have greater or less importance depending on the scale that you are considering. In my previous post, I used human-caused and natural effects on sediment regime to illustrate condition. Here I’ll continue to use that example to illustrate why a given indicator might need to be evaluated at different scales.

Figure 1. Near-stream road sediment loading along Spanish Creek, southeast of Quincy.

Soil type, which is dependent on parent geology, can be mostly similar across vast areas. The quality of soils, including how easily they erode, should therefore be considered at the landscape level i.e. the watershed scale.

Roads, similarly, are distributed across the landscape; there are roads developed everywhere, in a network, that get us where we need to be! So like soils, we should definitely examine their influence at the watershed scale. But, the number of roads has a greater impact in terms of the increasing fine sediment-load in a stream when they are located near the stream itself (Figure 1). So it is necessary to look at roads at another scale that captures this heightened influence on water and habitat quality.

One way to capture the effect of an indicator that is more important when it is closer to the stream is to examine its effect within a buffer. That is, within a given distance to the stream. Using our example, the number of roads within the buffer zone has more weight with regard to water and habitat quality. This is because the fine sediment eroded from the road surface or cut will immediately reach the stream channel whereas at the watershed scale the sediment is captured by vegetation. In order to develop and informed restoration strategy it’s necessary to examine indicators at multiple scales.

In practice, it is often hard to demonstrate precisely which landscape-scale characteristics affect in-stream conditions, yet we know that the landscape and land use across a watershed does affect in-stream condition. The natural landscape and human land use, over time, can act as a constraint or a destabilizing factor for restoration success. Looking at near-stream conditions allows resource managers to act on improving habitat in the short term by implementing restoration. However, doing so in a place where restoration results in lasting success depends on the landscape-scale characteristics that have to be examined at a larger scale.

Figure 2. Lower Indian Creek near Greenville, CA displayed at the (A) Watershed (B) Subwatershed and (C) Stream Buffer scales.

For the purposes of the UFRBWA, we anticipate looking at the indicators we select at three probable scales (Figure 2). The watersheds of the United States have been divided by the U.S. Geological Survey into a hierarchy based on surface hydrologic features. From this system, we anticipate examining indicators with landscape-level coverage and effect at the “Subwatershed” scale. Indicators such as those associated with projected climate change will likely be examined at the “Watershed” scale, the next step up. For indicators that have the most effect in the near-stream area we will likely developing a “reach scale” that segments streams and evaluates indicators in a buffer zone around those segments.

In short, selecting the right indicators is important for identify overall watershed condition, but because the effects and interactions between individual indicators varies across space and over time, it’s just as much a matter of scale!

EVOLUTION OF A FISHERY CONDITION ASSESSMENT PART II: WHAT IS CONDITION?

Road dips are a fish’s best friend.- Ken Roby

As I wrote about previously, the first Technical Advisory Team (TAT) Meeting of the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment and Improvement Strategy took place on April 19th, 2016 where we discussed next steps in the Assessment, namely how to assess overall condition of the watershed. Defining condition will help inform our end goals, which are to prioritize locations in the Upper Feather River Watershed for 1) conservation and 2) restoration.

Identifying the condition of a given area of the watershed will determine if the area should be slated for conservation, restoration, or not incorporated into project work. The areas with excellent native fisheries should be prioritized for conservation, i.e. protection, to ensure that they stay excellent. The areas that are more marginal but could be improved with some work should be targeted for, yes, RESTORATION!

So, since the TAT meeting, my project advisors and I have worked to synthesize the information generated in order to develop a framework for assessing the condition of different areas of the watershed. We started by developing a list of factors, or indicators, that cumulatively characterize the condition of a particular watershed and its fishery.

We know that a good indicator must fit a number of important criteria, namely:

- It must have a close relationship to fish habitat or distribution

- It must be measurable

- It must have an available data source

- It should have Basin-wide coverage

- It should have documented effect

A massive road failure in Umpqua National Forest. Credit: USFS

For example, let’s say we are interested in potentially using sediment as a condition indicator. We know that an excess of fine sediment is harmful to fish, with high amounts able to smother viable spawning gravels and even kill live fish like the juveniles produced by the Lake Almanor rainbow trout shown below (note that these fish were not actually harmed by any human activities). There are established methods of measuring both the natural dynamics of and anthropogenic influence on the sediment regime*, such natural soil erosion rates or road densities (which contribute to erosion). We also have very good data sources; soil characteristics have been mapped since the late 19th and early 20th century in United States Department of Agriculture initiatives related to food security and national productivity, including in our national forests! So, we therefore also know that we have Basin-wide coverage for data sources related to sediment. Additionally, there are many studies that have meaningfully documented the impacts of excessive sediment on water quality, and thus fisheries.

Well-designed and regularly placed dips on unpaved roads can prevent the accumulation of runoff that results in road failure. Credit: UN FAO.

So, it is safe to say that sediment is one good indicator for describing watershed condition. But, it is only one. There a numerous other factors that we know affect fishery condition that we must identify and include as condition indicators. These factors may be abiotic, that is completely physical phenomena like sediment or nutrients. Or they could be biotic, or living, such as the pathogens or introduced competitors that affect native fish.

Currently, the project facilitators have developed a working framework with a set of indicators that we believe is a good starting point for a meaningful assessment that reflects actual conditions in the Basin. This draft framework is under review by the Core Group of our Technical Advisory Team and will be finalized for work to begin in the coming weeks.

* “Sediment regime” refers broadly to the rate of sediment production, transport, and delivery; how much and where it comes from, where it goes, and where it ends up.

WHAT’S IN THE WATER!?

With just a few notes on the location where a water sample was taken and what species we might expect to find there, eDNA results can tell us a lot about the biodiversity of a given body of water!

The Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment and Improvement Strategy (UFRBWA) eDNA sampling effort is underway!

Environmental DNA, or eDNA, sampling consists of collecting water samples and filtering them for ambient DNA found in the water column. The filtered DNA samples are then analyzed in a laboratory setting to test for the presence or absence of a particular species, or sometimes even an entire assemblage. While the laboratory methods for analyzing eDNA have been long used in medicine, epidemiology, and other biological fields, utilization of field-collected samples to detect the presence of certain species from a water sample is a recent development. This novel application of eDNA technology makes it possible for resource managers to rapidly and efficiently sample for species presence across huge geographic areas, just as we plan to do in the UFRBWA!

Local resident John Fisher was surprised at how fast it was to collect a sample… We were surprised at how fast his boat could go! We finished sampling Frenchman Lake in 40 minutes flat!

So, on an April 21st pilot outing myself, TU Staff, and project advisor Mike Kossow sampled Lake Davis and Frenchman Lake, two reservoirs located in the eastern portion of the Upper Feather River Watershed. Lake Davis is a site of particular interest for sampling in the basin because non-native Northern pike (Esox lucius) were eradicated by California Department of Fish and Wildlife (CDFW) in 2007 in order to restore the reservoir’s trout fishery to its former excellence. Currently, we are approaching the ten-year mark since the Lake Davis eradication effort took place. CDFW plans to sample the lake by conventional means (i.e. boat electrofisher) for this milestone. Negative detection for pike in the results of both CDFW and our samples will confirm the success of eradication efforts without doubt.

During our outing we collected samples from 24 sites on Lake Davis and 6 sites on Frenchman Lake. These initial samples will be split and shipped to two separate labs for eDNA analysis. One lab, at Central Michigan University, will assess the entire fish assemblages in the reservoirs. Those results are expected sometime in the fall. Another analysis, to be conducted at the University of California, Davis, will yield faster results, a couple of months perhaps, as it tests specifically for the presence of Northern pike.

The largest of the three Upper Feather River reservoirs created as mitigation for the loss of recreation opportunities resulting from the construction of Oroville Lake, Lake Davis stands at approximately 4000 surface-acres with nearly 38 miles of shoreline when at it’s full capacity; plenty of places for a toothy invader to hide!

Frenchman Lake, like Davis, was created as mitigation for Lake Oroville (Antelope Lake is the third). It is also managed by CDFW primarily as a cold-water fishery. For the UFRBWA, the samples collected from both sites will be analyzed to determine the complete fish assemblage present.

Further eDNA sampling efforts under the UFRBWA will take place over the course of this summer. This will consist of a massive, geographic sampling protocol taking samples from water bodies across the Basin in order to determine the presence or absence of a suite of species.

Along with the results of the sampling at these first locations, results from the entire eDNA sampling will be examined alongside the conventional sampling survey record. Cumulatively, they will capture a snapshot in time of species distribution across the Basin, with the aim of helping agencies steer a variety of conservation and monitoring efforts in the future.

Dr. Jerde (left) and UFRBWA project advisor Mike Kossow couldn’t help themselves but to talk extensively about fishing in Montana, of course!

This initial effort was made possible with the help of Dr. Christopher Jerde, a Research Assistant Professor with the Department of Biology at University of Reno. Dr Jerde, along with his colleague Dr. Andrew Mahon at Central Michigan University, pioneered species surveillance using eDNA techniques while monitoring the spread of carp and other species in the Great Lakes Basin. Dr. Jerde has graciously offered to lend his experience and expertise regarding the applications of eDNA species surveillance with those involved in the UFRBWA effort.

Also credited are Trout Unlimited national staff member Mike Caltagirone and Feather River Trout Unlimited Chapter President Cindy Noble for their coordination help.

Ed Dillard (at the wheel) is an experienced local angling guide. He was more than willing to share his vast knowledge of species distribution in Lake Davis, helping us to decide what specific areas we should sample in!

Most importantly, I’d like to thank local volunteers who graciously donated their time and watercraft. Ed Dillard, of Dillard Guided Fishing, assisted us at Lake Davis and shared his vast knowledge of the fishery in the reservoir, helping to inform our sampling efforts. John Fisher, a local resident of Sierra Valley, assisted us at Frenchman Lake, helping us to collect our samples there with speed and style. Their assistance that day was invaluable.

And this is only just the beginning of what is sure to be a unique and groundbreaking application of eDNA technology!

EVOLUTION OF A FISHERY CONDITION ASSESSMENT

The first Technical Advisory Team (TAT) Meeting of the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Native Fish Assessment and Improvement Strategy took place on April 19, 2016. Our goals were to discuss next steps in the Basin-wide Fish Assessment to help inform our work defining fishery and habitat conditions in the Upper Feather River Basin.

Some 20 representatives from 5 agencies and organizations were in attendance including Trout Unlimited National, Trout Unlimited Feather River Chapter, United States Forest Service Plumas, Lassen and Tahoe National Forests, California Department of Water Resources, and the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

Those in attendance represented many of the fields of expertise most related to fisheries management, including not just fisheries biologists but hydrologists, water resource engineers, and geographers, to name a few. A subset of these individuals volunteered to be part of a Core Group of technical advisors for the Basin-wide Fish Assessment. While the larger group will help with brainstorming and big picture thinking, the Core group will help my TU advisors and me with the more detail-oriented discussion and planning for how these techniques will actually be implemented.

Specific goals of the meeting were to begin to identify framework approaches, habitat condition indicators, habitat condition risks, and the specific scale(s) at which the assessment will take place.

Discussion centered on techniques utilized in existing assessments that have taken place in the Basin and elsewhere, with a focus on identifying physical indicators that will cumulatively best define habitat condition. We also discussed the scale at which these physical indications, such as habitat connectivity, amount of habitat diversity, level of alteration to sediment regime, water quantity & quality, and fish assemblage composition (native v. non-native), have an effect on overall fishery quality and can be meaningfully analyzed. There was also a brief discussion on the applicability of these indicators to restoration goals i.e., identifying which indicators can feasibility be affected and improved by management decisions and efforts on the ground versus those which resource managers have little ability to influence. Additionally, we discussed briefly the primary risks to habitat condition in the future, namely regarding climate change and its probable ecological effects here in the Basin.

While myself and a few others felt that the meeting did not produce as concise of a consensus as desired in terms of obtaining a succinct list of habitat conditions indicators and specific metrics with which to analyze them, there was a broad sense amongst those in attendance that the main goals of the meeting were mostly reached. Additionally, there were a number of fresh ideas aired that had not yet been considered as well as recommendation of a number of data sources that we had not identified.

Most importantly, the group was able to identify 5 broad parameters to be examined in the assessment: 1) Water Quantity 2) Water Quality 3) Biological Community 4) Habitat Connectivity and 5) Risk and Vulnerability. Identifying specific metrics and data-sets for each parameter was tasked to the Core Group.

Overall, there was a definite value in drawing together so many managers and stakeholders. Being able to do so is evidence of the identified need and extraordinary level of support across the board for this effort. Many representatives from other agencies and fields were not able to attend but expressed their support for the effort, indicating a strong likelihood for growing attendance and participation in both the Core Group and larger team. The Core Group of the TAT will meet again in the second week of May while the larger group will meet sometime mid-to-late June.

FIRES, FISH AND A FEW SURPRISES: THOUGHTS ON THE PLUMAS NATIONAL FOREST INTEGRATED POST-FIRE RESTORATION SYMPOSIUM

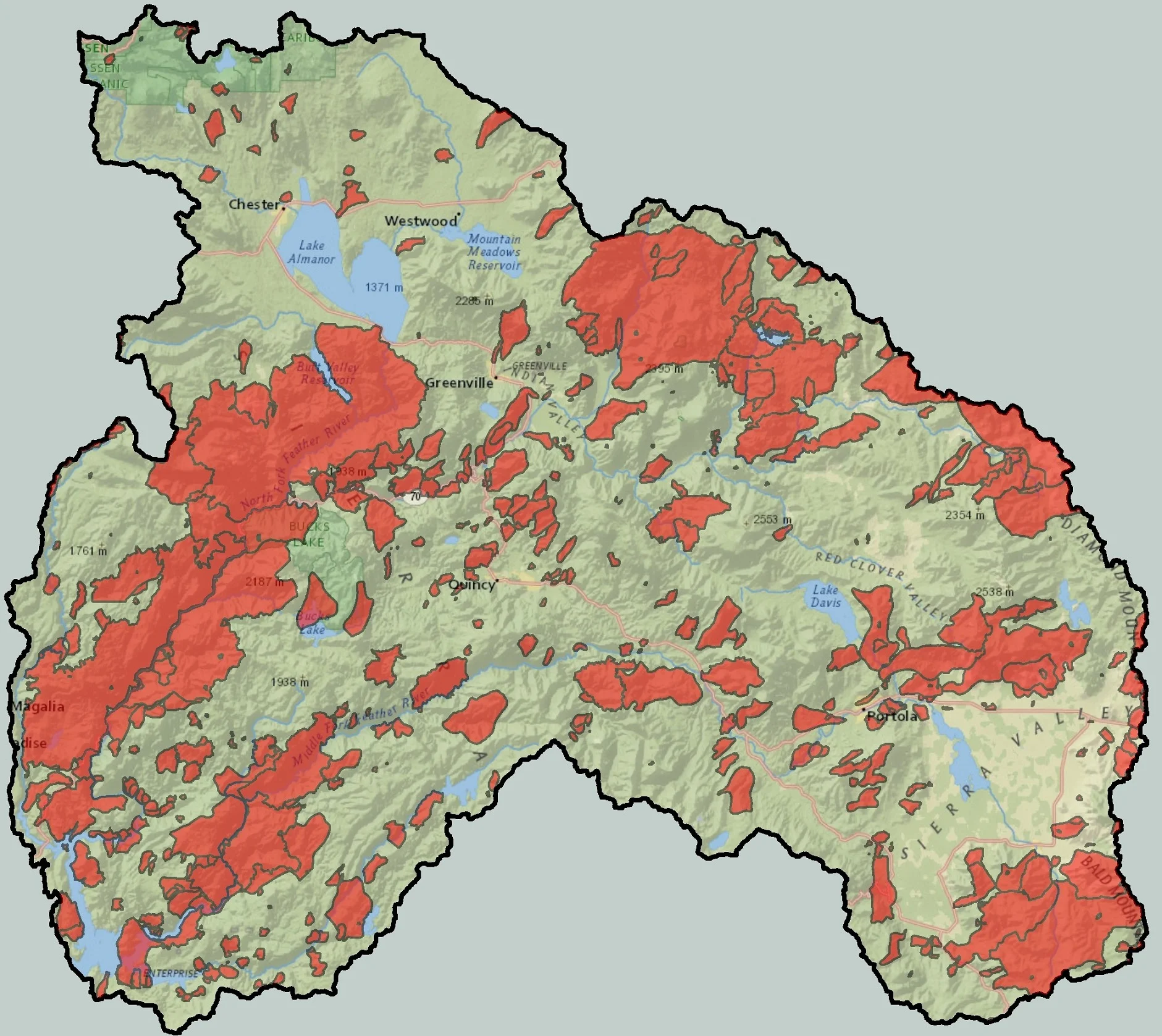

Wildfire footprint for the Upper Feather River Basin, 1900-2014

California’s recent history of unprecedented drought has brought along with it ever-increasing fire danger and subsequent disaster. With respect to fisheries, fire poses its own unique risks. High-severity fire can destabilize the soils in a basin, exacerbating the effects of sediment loading already caused by roads and other land-uses. Species like trout and other native fishes rely on cool, clean oxygenated water to survive and spawn. Turbid waters resulting from erosion degrade habitat by clouding spawning gravel and decreasing water quality, among other effects.

In areas with species that are endemic (native only to a localized area), severe fire and the resulting effects can mean extinction. In Southern California, where researchers are only just beginning to understand the complexity of the population genetics of steelhead in the region, the risk of fire-exacerbated mass wastage events could mean the loss of entire distinct populations before they are even defined. Furthermore, this is occurring even as conservation efforts work to remove dams to connect those populations back to the Pacific. This risk to fisheries caused by anthropogenic disturbance of fire regimes exists all across California, affecting the Golden trout of the Eastern Sierra to the redband trout of the McCloud River drainage in the southern Cascades. The Feather River country has experienced no exception from massive wildfire, and I recently had the opportunity to learn about ongoing research and assessment on post-fire landscapes that exist in the Basin when I attended the Plumas National Forest Integrated Post-Fire Restoration Symposium.

My primary interest of course was learning about work that was related to fisheries condition in the Basin. Some of the most exciting discussions relating to my own project included analysis of sediment loading from roads in high-severity fire footprints using the Geomorphic Road Analysis and Inventory Package (GRAIP), riparian zone response to fire and its effect on habitat, and the application of eDNA technologies in the detection of pathogens that affect trout here in the North Fork of the Feather River.

The roads analysis was undertaken to identify which road crossings and structures were most likely to fail and those that might have the greatest impact on water quality. The results will be used by the Forest to strategize maintenance and improvements of those critical segments of the road system in a cost effective manner.

Most exciting, perhaps, was the discussion on the application of eDNA analysis in the Feather River Watershed. Researchers from UC Davis sampled locations along the North Fork of the Feather River and its tributaries for the presence of two pathogens: Ceratomyxa shasta, which causes infections of the gastrointestinal tract and other afflictions; and Myxobolus cerebralis, the agent of whirling disease.

In the footprint of the Antelope Complex in the eastern part of the Feather River Basin.

Both species of pathogens utilize intermediate hosts, two species of worms, which inhabit sediments and soils. Fire, as mentioned above, can increase the influx of fine sediments to a stream channel. This can thereby increase available habitat for intermediate host species possibly resulting in increased spore counts.

The results of their research, though preliminary, seemed at first indication to be positive in two ways: 1) the detection rate of their eDNA sampling was quite good and 2) Myxobolus cerebralis was not detected. The intermediate host for M. cerebralis, the tubifex worm, was detected but was not of the variety that carries the M. cerebralis spores. This successful application of eDNA in detecting pathogens is significantly good news for the my project (the Upper Feather River Basin-Wide Assessment) organizers as we hope to apply eDNA sampling for these pathogens on a much wider scale in the Basin, possibly in partnership with these other researchers.

Another main takeaway was that while the aftermath of massive fires often looks disastrous, there is often more to these apparent moonscapes than meets the eye. What researchers have been discovering while working in the footprints of the Storrie, Chips Creek, Moonlight, and other fires in the Feather River Basin and across the state, is that post-fire landscapes are not ecological dead zones, but begin reestablishing surprisingly complex ecological dynamics almost as soon as the footprint cools. These dynamics are often found to be dependent not just on the time past since the fire occurred, but also the age and composition of the forest pre-burn and even on the severity of the fire.

So, attending the Plumas National Forest Integrated Post-Fire Restoration Symposium was very valuable in a number of ways. Looking through the lens of my own work it was useful in learning about the fire history of the Basin, the interaction of fire and aquatic habitat, and even provided a little bit of networking opportunity. More generally, the symposium really left me me with the sense that it is possible for agencies to embark on integrated management that truly accounts for the ecology of fire regime and it provided to me a new understanding of the surprising complexity of post-fire ecology.

ENGAGING COMMUNITIES IN THE SCIENTIFIC PROCESS…

Community engagement and analysis of benefit and outcome are integral elements of the scientific process.

Basin-wide Fish Assessment and Community Coordination Fellow

The title says it all. “Community Coordination Fellow” is one clause of my Sierra Fellows title and so it occurs to me that it is necessary to identify exactly how to engage my host community in my work, which is, of course, supposed to benefit them… somehow…

Science should and simply does have a community element. Especially when the topic of research is highly important to a community (or even a society), people care about what the results of a scientific endeavor will be, and how these results might influence their daily lives. In the Upper Feather River Basin, desirable fishery management outcomes can be quite different for any given person. An avid angler that fishes every possible day for not just success, perhaps, but setting and the joy of pursuit, will have concerns and opinions that are somewhat different than the summer visitor who wants to ensure their children catch anything at all. For the angler, a colorful native rainbow might be the objective. For the visitor, a child’s smile. They, in turn, have different interests than the shop owner who relies on their business, or the rancher who uses the angler’s same stream as a water source for her cattle.

For this and many other reasons, it is appropriate and necessary for the UFRBWA to have a community coordination aspect. From the land management perspective, there are many resources managers responsible for fisheries management or monitoring in the Basin, and many more responsible for the management of resources that affect fishery health in less direct ways. Coordinating with all of these folks is necessary in order to maximize inclusion of the diverse expertise these parties represent, as well as the data they, or their agency is privy to. Coordination also ensures that management strategies have a resource perspective, i.e. the fish, rather than a particular agency’s objective or a particular funding source requirement. It also means that strategizing occurs at a larger scale such that it can first identify the priority areas before investing resources into areas in which only marginal protection, reconnection and restoration is possible.

Additionally, the Basin is home to numerous communities that, while similar in a broad sense, are quite diverse in their composition, opinions, priorities, and the resulting overall perspectives they represent. Furthermore, I have found each community area to contain various groups interested in many ways with fishery health. Coordinating with and integrating these groups, which may include local business owners, educators, rangeland managers and, of course, anglers (among others), into my project activities will be necessary in order to ensure their voices are heard in project steering as well as to develop a broad base of community support for this work.

Because I now live in the communities that are affected by my work and I endeavor to be liked and respected in them, I will have to navigate this engagement so as not to adversely affect my research or standing in the community. Additionally, it may be necessary to shift roles in order to engage all of the stakeholders (including those whose stance may directly contradict with my project or personal goals), creating further issues regarding expectations.

As I work towards engaging my host community, I find myself seeking the most effective and productive course but am often confronted with questions about how to go about this. What responsibility do I have in my work to help a community address or resolve problems or conflicts, or create expectations? How can I engage and acknowledge the community’s preferences and expectations such that there is equal representation in my work? And what if, for example, the results of my work show the need for discontinuing a favored management practice?

Many of these questions will remain unanswered until I am able to fully immerse or acquaint myself in the community perspectives. In order to do so, I plan to host community engagement meetings. These will take place as town hall-style forums in which I will present 1) an overview of the project, its needs and goals 2) progress and information generated to date and 3) solicit from the public any concerns or desires they have regarding the focus or process of my work.

From just a short time of living in Plumas County communities, I have been able to discover the importance that fish (and wildlife) management has for many residents in the area. As I’ve met more and more of those members and have begun engaging them through conversation, I have further realized that there is also great diversity in local opinions with respect to my work. While oftentimes a given group will feel strongly about a certain course of fisheries management (and strongly against an opposing group’s view), what I have found to be consistent across all groups is that the opinions of individuals in the community cannot be lumped in categories, but rather lie along a broad spectrum of priorities, ethics, and desired outcomes. Engaging the entire spectrum, though challenging, will be key to assisting the communities in developing a unified set of objectives for improving fishery health in the Basin.

While addressing community coordination for UFRBWA does have an easily defined path for initial community engagement (representative interview pools, town hall steering meetings, etc.) it seems that, much like the scientific method, community coordination will be an iterative process, in which we revisit our results until they stand with rigor as solutions that are broadly approved of by the community at large.